Lafarge’s decision to keep its Syrian cement plant running during the Syrian Civil War led to secret dealings with armed groups, including U.S.-designated terrorist organizations, triggering one of the most significant corporate accountability cases of the past decade.

In 2022, Lafarge pleaded guilty to providing material support to terrorist groups after the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) found it had funneled nearly $6 million to the Islamic State of Syria (ISIS) and the al-Nusra Front (ANF) using U.S. financial systems and email services—the first corporate case of its kind in the U.S.

Lafarge’s Syrian plant started unassumingly, but the ordinary venture soon entangled the company in serious legal and ethical challenges.

Background

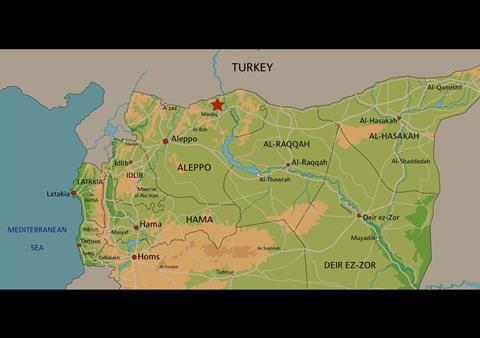

In 2010, Paris-based Lafarge built a cement plant in the Jalabiyeh region of Syria for $680 million—the same year the Arab Spring began in Tunisia. The plant, a subsidiary called Lafarge Cement Syria (LCS), operated at a loss much of the time, according to Holcim.

Political unrest reached Syria in March 2011, where peaceful protests swiftly turned into civil unrest. Riots led to escalated violence from authorities, which led to the formation of the Free Syrian Army against the Syrian government. An influx of armed factions and rebel groups, including jihadist terrorist organizations ANF and ISIS, gained control of surrounding areas. The geopolitical situation kept deteriorating. Chaos reigned.

The United Nations (U.N.) declared Syria in a state of civil war in December 2011, stating more than 4,000 people had died since March of that year.

Operating in a war zone, the LCS plant was plagued by significant challenges. From the beginning, it faced steep competition from Turkish cement importers, according to the Justice Departmentʼs 52-page statement of facts. Then, in September 2011, the European Union imposed an embargo on Syrian petroleum products, severely weakening the Syrian economy.

But while other companies pulled out of Syria in response to the EUʼs sanctions, Lafarge tried to keep the LCS plant in business. By May 2012, violent conflict had spread to areas immediately surrounding the plant. Some LCS employees were kidnapped for ransom, one LCS contractor was killed at a checkpoint, and armed militants began to regularly hijack LCS trucks, the DOJ found.

Lafarge and LCS executives were aware of the risks of violence to their personnel and suppliers, the DOJ stated. To deal with these problems, Lafarge executives made two major decisions in the summer of 2012.

The first was to evacuate LCSʼs European employees from the country, whom they believed were targets, and relocate them to Cairo, Egypt. The second was to begin negotiations through intermediaries with various armed factions in the Syrian Civil War to permit continued operations of the Syrian plant, both Holcim and the DOJ learned.

LafargeHolcim said that local managementʼs decision making was rooted in the belief that “it was serving the best interests of the company and its employees who depended on LCS salaries for their livelihood,ˮ according to the 2017 press release outlining the results of its independent investigation.

“In hindsight, any misdeeds may seem clear. However, the combination of the war zone chaos and the ‘can-doʼ approach to maintain operations in these circumstances may have caused those involved to seriously misjudge the situation and to neglect to focus sufficiently on the legal and reputational implications of their conduct,ˮ LafargeHolcim stated.

The DOJ, for its part, acknowledged that ISIS and ANF would have used force and threats of force against LCSʼs employees and customers had LCS refused to deal with them. However, the DOJʼs investigation also pointed out another incentive for misconduct beyond security interests: Lafarge negotiated with ISIS and ANF to obtain economic advantage over their Turkish competitors in the Syrian cement market.

The Evolution of a Scheme

The CEO of Lafarge’s Syrian subsidiary (not the global CEO) stated that security payments were “local concessions” approved by his superiors. This information comes from a 2017 letter he wrote after being fired, which the U.S. government obtained. Lafarge and LCS executives reportedly concealed these concessions using middlemen, false invoices, and by labeling them as “donations.”

Initially, payments were made to armed groups that were not U.S.-sanctioned entities. The Democratic Union Party in Syria (PYD), which is not a U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organization, was listed internally as a “beneficiary” receiving “donations,” according to the DOJ. However, as U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) like ANF and ISIS grew in the vicinity of the plant, Lafarge executives faced the difficult decision of whether to continue operations or withdraw.

Notes from a September 2013 meeting, obtained by the DOJ, show Lafarge and LCS executives acknowledging the increasing difficulty of operating without directly or indirectly negotiating with groups classified as terrorists by international organizations and the U.S. An internal email, also obtained by the U.S. government, suggested that the prospect of writing down their $680 million investment was unappealing. In a March 2014 email, an intermediary asked three top executives—Lafarge’s Vice President of Security, Lafarge’s Executive Vice President of Operations, and the CEO of LCS—if Lafarge could bear a loss of approximately $600 million due to the challenging situation.

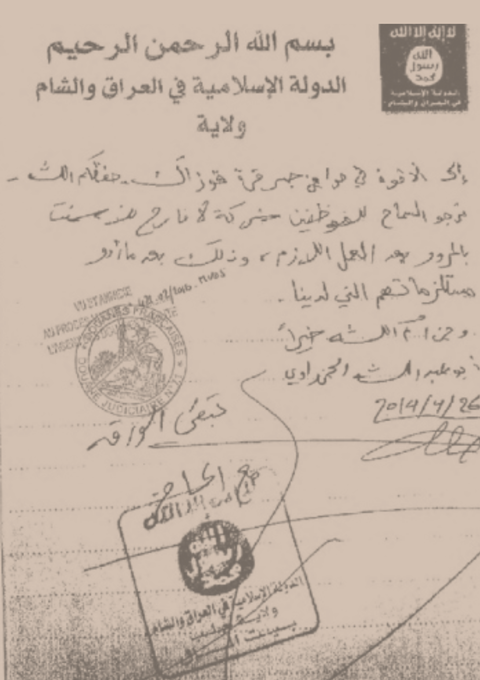

The cement maker remained and negotiated more contracts with U.S.-terrorist organizations to further their “operations,” as Holcim (then LafargeHolcim) stated, and in furtherance of their “conspiracy,” as the DOJ put it. They took care to ensure documents regarding payments to FTOs and other armed groups did not reference “Lafarge,” according to the Justice Department.

In August 2014, Lafarge also entered into a revenue-sharing agreement with ISIS, as found by the DOJ. The company agreed to pay “taxes” to ISIS based on the volume of cement sold by the plant. In return, ISIS agreed to grant Lafarge access to raw materials, allow the company’s personnel, suppliers, and customer-distributors to pass ISIS and ANF checkpoints without incident, and even keep Turkish competition out of the market, according to internal emails obtained by the U.S.

About a year later, Lafarge completed a merger of equals with Holcim. In July 2015, the two companies launched a new brand and corporate identity: LafargeHolcim.

In February 2016, Syrian news outlet Zaman al Wasl published investigative reports indicating that Lafarge—now LafargeHolcim—had been buying oil from ISIS. Leaked documents, reportedly from Lafarge’s internal communications, showed that the company had negotiated agreements with ISIS to protect its employees, customers, and suppliers for safe passage and had procured supplies from ISIS-controlled entities. The news report also included partially redacted images of emails sent to and from Lafarge executives’ accounts, discussing payments to ISIS. The DOJ later found inculpatory emails similar to those published by the Syrian media, which exposed written agreements to buy pozzolana and fuel oil from ISIS-controlled suppliers, and safe passage contracts with ISIS.

LafargeHolcim’s head of compliance became aware of al Wasl’s allegations in February 2016 and informed the company’s Chief Legal and Compliance Officer (CLCO), the DOJ learned. The CLCO engaged a U.S. law firm to conduct a legal analysis of the allegations, which was presented on May 11, 2016. That same day, the CLCO informed the finance and audit committee of LafargeHolcim’s board of directors, who directed him to conduct an investigation.

The unraveling began, and LafargeHolcim rebranded itself Holcim Group in July 2021.

A spokesperson for Lafarge commented: “As we have said previously, this is a legacy Lafarge issue from more than a decade ago, which Lafarge is addressing through the legal process. None of the conduct involved Holcim, which has never operated in Syria and did not own Lafarge at the time the conduct occurred.”

The DOJ noted in the statement of facts that former Lafarge and LCS executives involved in the conduct attempted to conceal it from Holcim before and after Holcim acquired Lafarge in 2015, as well as from external auditors. The DOJ also noted that Holcim “had put in place an effective compliance program reasonably designed and implemented to detect and prevent any potential future criminal conduct like that committed by LAFARGE and LCS.”

No comments yet