January 22, 2015.

It was a bitterly cold day, the temperature near freezing, when two senior leaders from Deutsche Bank came knocking on the 15-foot oak entry doors of Jeffrey Epstein’s New York town house.

The financial advisers were there on pressing business. Certain issues involving the customer’s accounts had been escalated by the bank’s anti-financial crime department, and the gentlemen were there to give the convicted pedophile a chance to address them—discreetly.

The irony of holding the meeting in Epstein’s multimillion-dollar town house, where countless acts of sexual abuse and commercial sex acts had taken place, strikes with the force of 20-20 hindsight now. It might have been lost on the Deutsche Bank employees on that day. However, they were at least aware of one accuser’s claim of abuse at that location.

In winter 2015, the legal and factual bases for claims against Epstein’s financial institutions (FIs) for know your customer (KYC) and customer due diligence (CDD) failures were far from certain. That reckoning would come years later.

Epstein, who loved his privacy, was back in the headlines. His 2008 conviction of solicitation and procurement of a minor to engage in prostitution was inconveniently resurfacing. The restoked heat was precipitated by a federal appeals court having ruled certain victims would be granted access to the details of his plea bargain, potentially reopening their cases.

At the same time, fresh allegations of sexual abuse and trafficking were trending. A woman named Virginia Giuffre had just revealed publicly that, while a minor, she was trafficked by Epstein and forced to engage in sexual activity with his friends, including a member of British royalty, in London, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and New York.

All the brouhaha in the media was raising eyebrows at Deutsche Bank.

An anti-money laundering (AML) compliance officer, who was aware of the press reports, escalated these and other concerns up the chain, culminating in the decision that Deutsche Bank’s Americas reputational risk committee (ARRC) would meet to determine whether the Epstein relationship should be terminated.

The house call occurred in preparation for and days ahead of the ARRC meeting. The two senior leaders at the bank who met with Epstein were Paul Morris and Charles “Chip” Packard.

A Jane Doe lawsuit alleging racketeering against Deutsche Bank by some of Epstein’s victims identified Morris as Epstein’s relationship manager in the bank’s private wealth department. He came to Deutsche Bank from JPMorgan Chase in late 2012, the timing of which was no coincidence: He had been a member of the team servicing Epstein’s accounts at JPMorgan.

Packard was identified as co-head of Deutsche Bank’s wealth management Americas group at the time of the 2015 home visit. He was involved in approving Epstein as a client during initial onboarding and, along with Morris, maintaining him as a client once the relationship began.

That notes were omitted during a so-called due diligence meeting and that apparently no other steps were taken at the time to investigate the veracity of the allegations beyond believing Epstein at his word are prime examples of bank leaders and high-ranking employees undermining KYC and AML procedures.

A consent order Deutsche Bank reached with the New York State Department of Financial Services (NYDFS) in July 2020 regarding the bank’s dealings with Epstein did not name either Morris or Packard but described the actions of an unnamed relationship manager and relationship coordinator during the relevant time frame. The relationship manager suggested to senior management in an email that Epstein was a potential client who could generate “‘[e]stimated flows of $100-300 [million] overtime [SIC] (possibly more) w/ revenue of $2-4 million annually over time,’” as well as leads for other lucrative clients. The relationship manager recommended at the outset that all Epstein-related accounts be for “‘entities’” affiliated with Epstein, “‘not personal accounts,’” according to the NYDFS order.

By August 2013, Epstein had been officially welcomed as a high-risk, high-net-worth client at Deutsche Bank.

The men held their meeting at a bar next to Epstein’s indoor swimming pool, according to the Doe lawsuit. Packard asked Epstein questions relating to the concerns raised by the AML compliance officer. There is no easy way of knowing how “in the weeds” the questions were. In theory, he might have touched on any of the following red flags detected in Epstein’s account activity:

- Periodic large cash withdrawals—on average, more than $200,000 per year;

- Payments to Russian models and numerous women with Eastern European surnames;

- Payments for women’s school tuition, rent, and hotel expenses; or

- Payments to individuals like Ghislaine Maxwell and others who were publicly alleged to have been co-conspirators in sexually abusing young women.

Packard purportedly asked Epstein about the veracity of new allegations in the press: Was he, Epstein, involved in sex abuse and sex trafficking, as Giuffre and others alleged?

Epstein’s responses to Packard’s inquiries are lost to history. No contemporaneous notes were taken during this meeting. The reputed takeaway was that he denied the allegations. Whatever explanation he provided was apparently sufficient to satisfy the bankers’ concerns.

Morris and Packard did not respond to requests for comment on the details included in the Doe lawsuit.

That notes were omitted during a so-called due diligence meeting and that apparently no other steps were taken at the time to investigate the veracity of the allegations beyond believing Epstein at his word are prime examples of bank leaders and high-ranking employees undermining KYC and AML procedures.

One week after the house call, the ARRC held its meeting to determine whether to terminate the Epstein relationship. Again, no minutes were recorded, contrary to bank policy and procedures.

Later that day, a member of the ARRC emailed their decision.

The message was short and sweet: The committee was “‘comfortable with things continuing’” with Epstein, according to the NYDFS’s order. While no explanation for the decision was given, the email mentioned how another member of the committee had “‘noted a number of sizable deals recently.’”

Thus, the Epstein relationship carried on at Deutsche Bank for a time.

In November 2018, the Miami Herald published an explosive exposé on Epstein, detailing the magnitude of his sex trafficking operation in which 80 potential victims were identified, his 2008 plea deal and exceptionally light sentence, and a non-prosecution agreement secretly negotiated by then-U.S. Attorney Alexander Acosta that gave Epstein and his named and unnamed co-conspirators immunity from federal prosecution.

A harsh spotlight had been shone on the man. The reputational risks of continuing with Epstein as a client were too high for Deutsche Bank to tolerate.

On Dec. 21, 2018, Deutsche Bank informed Epstein by letter the bank would no longer be servicing his accounts.

In July 2020, the NYDFS imposed a $150 million penalty on Deutsche Bank for its dealings with Epstein, among other, separate compliance failures. In its consent order, the NYDFS reprimanded Deutsche Bank for its procedural failures in how it managed and oversaw the Epstein relationship.

“We acknowledge our error of onboarding Epstein in 2013 and the weaknesses in our processes. We have learnt from our mistakes and deeply regret our association with Epstein,” the bank wrote on Twitter, now called X, at the time.

We acknowledge our error of onboarding Epstein in 2013 and the weaknesses in our processes. We have learnt from our mistakes and deeply regret our association with Epstein.

— Deutsche Bank (@DeutscheBank) July 7, 2020

Morris, the relationship manager who helped usher Epstein into Deutsche Bank in 2013, was long gone. He left for a competitor’s private wealth management division in 2016. Packard packed up as well, having moved to a hedge fund that same year.

In the end, the bank processed hundreds of transactions totaling millions of dollars of Epstein’s money.

The bank’s parting courtesy to Epstein was to draft reference letters to two other FIs. On Deutsche Bank letterhead, Epstein’s new relationship manager penned one such letter. In it, he stated he was “‘unaware of any problems relating to the operation or use of [the] accounts,’” according to the NYDFS order.

When profit centers ‘rule the roost’

Deutsche Bank’s home visit to Epstein’s town house and the subsequent ARRC meeting represented a missed opportunity for the institution. Epstein had been a high-risk client for 2 1/2 years by that stage, and while his surface-level appeal was obvious—he was worth hundreds of millions of dollars in assets and boasted an impressive network of friends in high places—he raised countless red flags from the start. His reputation for trafficking and abuse of young women had been well-documented by 2013.

It was never the case that Epstein pulled the wool over Deutsche Bank’s eyes. The bank knew the man’s history and properly classified him as “high risk” because of it, resulting in enhanced due diligence during onboarding. Because of his connections to prominent political figures, the bank additionally coined him an “honorary” politically exposed person—an invented designation—which nevertheless resulted in enhanced transaction monitoring, technically speaking.

The Epstein enterprise

The late Jeffrey Epstein, who died by apparent suicide in a federal jail cell in 2019 while awaiting trial on sex-trafficking charges, has posthumously acquired several fetching monikers:

Disgraced financier.

Pedophile.

Monster.

The enormity of Epstein’s depravity remained largely hushed in his lifetime. He was registered as a sex offender in two states, including a Level 3 (high risk) designation in New York, and had on his record a 2008 conviction of solicitation and procurement of a minor to engage in prostitution. Yet, he managed to dance between the raindrops for years, leading an intensely private life in the lap of luxury while operating his enterprise in the shadows. Only in the years since his death have his crimes been more fully exposed, his victims vindicated, and his collaborators held accountable.

The enterprise in question was not financial advisory services for the ultrarich, even if Epstein dabbled in that area. It was not “cutting edge consulting services” in “biomedical and financial informatics,” as one of his companies purported to offer. It was a criminal sex trafficking enterprise with international operations.

If the logistical inner workings of Epstein’s life seem elusive, they were. How Epstein divided his time between his legitimate and ignoble enterprises—that is, whether he was a full-time financier and part-time predator or just the opposite—is difficult to say, let alone prove.

Epstein was anything but the typical human trafficker. He appeared to be motivated less by financial gain than a thirst for untouchability and power.

“Human trafficking is a for-profit activity. Epstein was already quite wealthy when the allegations against him started. … [T]he trafficking of the girls and young women seemed to be about something other than profit, other than a means to make money,” said Ola Tucker, an experienced compliance professional with a career focus on financial crime compliance and risk management.

The precise number of Epstein’s alleged victims is unknown. Brushstrokes of the truth have emerged over time, slashing together the portrait of a compulsive sexual predator. Dozens of Epstein’s accusers, some by name and others as Jane Does, have stepped forward to provide accounts of their experiences.

Preceding his death, Epstein was involved in 17 out-of-court civil settlements related to his conduct in his 2008 conviction. By 2011, 40 underage girls had come forward with testimony of Epstein sexually assaulting them. When a grand jury indicted Epstein for sex trafficking and conspiring to do the same in 2019, it found he had sexually exploited and abused dozens of minor girls from at least 2002 through at least 2005 and had paid certain victims to recruit additional underage girls whom he could similarly abuse. Like a spider weaving its web under the cover of darkness, he caught and immobilized his prey while creating a network to ensnare future victims.

Three months after his jail cell death, the Epstein Victims’ Compensation Program (EVCP) was established to help pay restitution to his victims. The fund, which was initiated by overseers of Epstein’s estate, then valued at $635 million, received more than 200 claims from women accusing Epstein of abuse.

Even these numbers could understate the totality of his victims. For one thing, the grand jury’s finding was restricted to a period of approximately four years and concerned only minors, not adults. For another, participation in the EVCP was voluntary.

Even spiders must be tethered to some support to build their egocentric world. Epstein could not, and did not, grow his enterprise on his own. As the legal team representing a class of Epstein’s victims pointed out, he needed a financial institution (FI) to provide the financial underpinnings of his venture. In their words, he needed a bank that would “provide the necessary legitimate appearance for his operation, allow him to open many accounts for illegitimate companies, ignore red flags, ignore federal banking laws, allow him to transfer money without questioning, allow him access to abundant cash, and to otherwise facilitate the commercial aspect of his commercial sex trafficking enterprise.”

For more than two decades while Epstein’s sex trafficking enterprise rapidly grew, he banked sequentially with two prominent FIs: JPMorgan Chase and Deutsche Bank.

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO statute, makes it a federal crime to conduct or participate, directly or indirectly, in a criminal enterprise. An enterprise, as defined in RICO, includes “any individual, partnership, corporation, association, or other legal entity, and any union or group of individuals associated in fact although not a legal entity.”

When Jane Doe and other Epstein accusers brought a class-action lawsuit against Deutsche Bank in 2022, the group’s attorneys alleged the bank and its employees constituted an enterprise under the RICO definition. By ignoring red flags, the bank acted as an accomplice in sustaining Epstein’s sex-trafficking enterprise, providing the requisite financial support for its continued operation from 2013-18. In May 2023, Deutsche Bank agreed to pay $75 million to settle the suit.

At the time of the settlement, Deutsche Bank did not provide comment. It did not respond to a request for comment for this report.

And, of course, before Deutsche Bank, there was JPMorgan.

Epstein was a client at JPMorgan from about 1998 to 2013. Like Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan and certain of its high-ranking employees purportedly turned a blind eye to Epstein’s suspicious activity, enabling and benefiting financially from his sex trafficking enterprise. A class-action lawsuit against JPMorgan brought by Jane Doe and other Epstein accusers in 2022 led to a June 2023 settlement of $290 million for the victims.

“The parties believe this settlement is in the best interests of all parties, especially the survivors who were the victims of Epstein’s terrible abuse,” said JPMorgan and the legal representatives of the female victims in a joint statement at the time.

“Given where the case law now stands, financial institutions will need to carefully review their policies and practices to ensure that they are actively spotting the key markers of criminal sex trafficking activity,” one of Jane Doe’s attorneys, Sigrid McCawley, told Compliance Week.

JPMorgan did not respond to a request for further comment on this settlement.

“While [Deutsche Bank] did these things at a high level—with the customer onboarding and recognizing the need for enhanced due diligence—it appears they failed in actually properly doing enhanced due diligence,” Maria Vullo, former superintendent of the NYDFS (2016-19), told Compliance Week.

Whether it was down to communication breakdowns, procedural errors, office culture issues, or some combination thereof, the bank failed to tailor the transaction monitoring of Epstein-related accounts based on the risk. Suspicious transactions were routinely cleared, and persistent red flags brought to the attention of high-level executives were explained away.

“I think what’s really important [to ask] is … why were decisions made the way they were made internally in the bank?” Vullo said.

Evidence points to a cultural tension: a tug-of-war between the allure of profit and the drag of compliance, with the former having all the pulling power.

“There was discussion about the amount of profit from this customer (Epstein),” said Vullo, reflecting on the NYDFS order. “… The initial onboarding documentation included a discussion of the expected profit or certainly a concept of, ‘We’re going to make a lot of money from this account.’ So, did that profit motive overtake the compliance concerns?”

Jeremy Swetenham, senior customer success manager at AML and KYC technology provider KYC360, also called attention to the email the first relationship manager cited in the NYDFS order sent in 2013 dangling Epstein’s “‘estimated flows’” of hundreds of millions to bank leaders.

“Within the financial services industry, you’ve got targets to meet. You want to get the revenue, and the business wants to book the revenue. … So [the relationship manager] is saying he’s trying to speed it up and prioritize this [relationship] by saying it’s lucrative. … The driver is to get the money in,” he said.

Friction between front-office personnel and compliance/risk management staff is normal, healthy even, when managed strategically. However, a tilt in checks and balances can lead to systemic weaknesses, such as in KYC and AML procedures, and poison the culture.

“The way most banks are structured, compliance and [human resources] are cost centers, not profit centers. At the end of the day, the profit centers rule the roost, even if it’s not the recommended view,” said Jamie Fiore Higgins, former managing director at Goldman Sachs.

Pressure is often placed on compliance staff to avoid exiting high-net-worth clients, according to a former AML compliance employee at an FI. Given the sensitivity around any perceived association with Epstein, he spoke on the condition of anonymity.

The burden of tact falls on compliance to navigate the internal politics of, “How do we not exit this person or how do we deal with the business who’s insisting that we keep this individual or this organization that’s clearly showing negative concerns?” the former AML compliance employee said.

Higgins, who worked on Wall Street for nearly two decades, described toxic culture as operating on two levels.

“There is a veneer of how [FIs] want things to look and then there is an underbelly of how things actually look. And I would say that is the same for any bank on Wall Street,” she asserted.

That state of affairs does not happen overnight; it is usually a series of missteps that incrementally leads to culturally impoverished outcomes, she said.

“If you have enough people breaking small rules, not taking rules seriously, it culminates into something bigger,” Higgins said. “Everyone [in FIs] is constantly inspired to push the envelope.

“I can assure you [FIs] are doing all the [Securities and Exchange Commission]-mandated training, self-paced webinars, and some such. All the boxes are ticked. The biggest theme here is that compliance raised concerns and then they were squashed. How can compliance people truly do their job when they are pushed around by the powers that be?”

Winter 2015 could have been a culturally transformative moment for Deutsche Bank, one where executives heeded the revitalized warnings of risk management staff and terminated the Epstein relationship then and there. That is not what happened. High-level leaders appeared to overrule issues escalated by the bank’s AML compliance staff and maintain business with Epstein for nearly four years thereafter.

“The compliance people actually did their job to some extent by bringing up [the red flags]. The problem was that the higher-level businesspeople whose focus was profit were the ones that basically told compliance, ‘No, it’s OK. We talked to the guy,’” said Vullo.

“When the first line gives that information, compliance can still say, ‘No, that’s not good. I need more details.’ And here [at Deutsche Bank], it seems to have been much more lax, which is reflective of their culture,” she said.

Rebalancing the scales

Deutsche Bank’s AML compliance staff raised concerns intermittently throughout the Epstein relationship, according to the NYDFS order. Various personnel flagged multiple, separate issues every year Epstein was a customer, from ongoing KYC concerns each time he opened a new account, of which he had more than 40 by 2019, to recurring suspicious transactions.

For example, Epstein’s attorney triggered currency transaction reports (CTRs) on numerous occasions whenever he withdrew more than $10,000 in cash from an Epstein-related account—or when he broke up transactions over two days to avoid CTR filings, an act constituting the federal crime of structuring.

Each time concerns were escalated by AML compliance staff to senior management, or CTRs were filed by bank personnel to the U.S. Treasury Department, the efforts appeared to be in vain. Ultimately, the bank never sought or received further explanation for the cash activity beyond “travel, tipping, and expenses,” according to a one-off email from said attorney cited in the NYDFS order.

For compliance to protect the organization from external risk, the organization must protect compliance from internal subversion. The sovereignty of the compliance function must be upheld both culturally and structurally.

To that end, three things must occur:

- A culture of compliance must be established from the top down;

- Compensation for compliance personnel must be equivalent to counterparts in other business areas (i.e., “profit centers”); and

- Compliance must have a direct line to the company’s independent board of directors.

To the first point, the criticality of building an organizational culture of compliance cannot be overstated.

“It comes from the top, but it has to be real … and it also has to filter down to middle management,” Vullo explained. The manner in which executives speak about compliance, even or perhaps especially in passing, carries weight.

“It can’t be, ‘Oh, we hate regulators. Oh, this is horrible. Oh, this costs so much money,’ because that trickles down to the employees in an institution,” Vullo said.

Blatant disparagement of compliance is obviously a culture killer but so is quiet negligence. Ola Tucker, an experienced compliance professional with a career focus on financial crime compliance and risk management, stressed the correlation between cultural laxity and heightened regulatory risk. A tick-box attitude around compliance can lead to a dearth of adequate resourcing, setting the function up for failure.

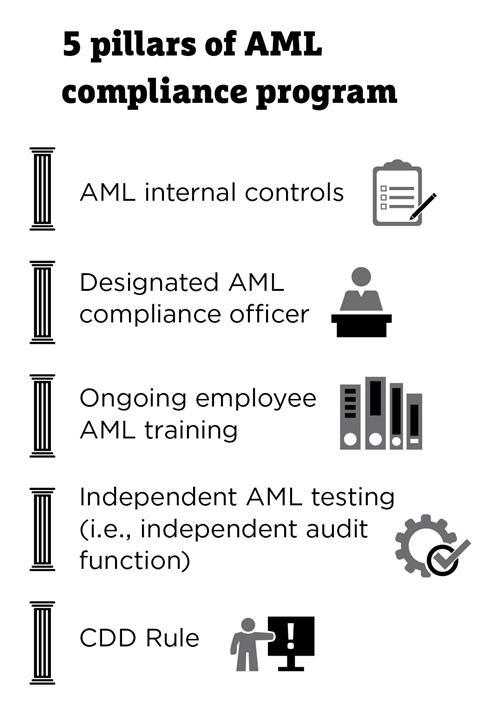

“One of the five pillars of an AML compliance program is a dedicated compliance officer but not just that,” Tucker said. “The dedicated compliance officer has to have the correct level of training, seniority, resources, and support to enable them to properly and effectively do their job.”

Bank leaders who fail to foster an organizational culture of compliance will likely find deficiencies in one or more pillars of their AML compliance programs, often resulting in regulatory fines and penalties or enforcement actions, Tucker asserted in her book, “The Flow of Illicit Funds: A Case Study Approach to Anti-Money Laundering Compliance.”

Secondly, compliance must be compensated comparably to other business areas to establish its authority and balance the scales of influence organizationally. Incentive compensation—i.e., compensation based on financial metrics—creates a culture of profit, Vullo noted.

“Compliance, legal, risk management—those are people that are not directly tied, and should not be tied, to profit,” she said. “But the question, then, is always: ‘What’s their authority?’ When I see things like, ‘Oh, the compliance officer escalated it and then the relationship manager basically overruled the compliance officer,’ I see profit winning over compliance just in that situation.

“If [compliance officers] don’t feel that they have sufficient independence, sufficient resources, and sufficient connection to where their job falls within the organization, and then you have a senior executive [overruling them] who earns a huge amount of money for the institution, the compliance officer may feel like, ‘What can I do? I raised it. I protected myself, but I can’t do anything about this.’”

Finally, and relatedly, compliance must have direct access to the institution’s independent board of directors.

“In fact, it’s the board of directors that bears the ultimate responsibility for ensuring … that the company is in compliance,” Tucker pointed out. “The compliance officer should regularly report the status of ongoing compliance to the board of directors and senior management so that the board and senior management can make informed decisions about the existing risk exposure.”

Vullo called a direct line to the board a “critically important protection for compliance.” Alluding to Deutsche Bank, she said, “It is structural governance that helps compliance officers not get overruled.”

Read on—Chapter 2: KYC shortfalls: JPMorgan and Deutsche Bank’s onboarding of Epstein

Topics

- AML

- Anti-Corruption

- Banking

- Boards & Shareholders

- Case study

- CDD

- Compensation

- Currency Transaction Reports

- Customer Due Diligence

- Deutsche Bank

- Epstein KYC/AML Case Study

- Ethics & Culture

- Europe

- Europe

- Finance

- Financial Services

- Internal Investigations

- Jeffrey Epstein

- JPMorgan Chase

- Know Your Customer

- KYC

- New York State Department of Financial Services

- NYDFS

- Risk Management

- Surveys & Benchmarking

- Suspicious Activity Reports

- United States

Case study: ‘The Banks Behind the Epstein Enterprise’

This Compliance Week case study offers a deep dive into the anti-money laundering compliance failures—and alleged complicity—of JPMorgan Chase and Deutsche Bank, the two banks that enabled the Jeffrey Epstein enterprise to flourish for decades.

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Chapter 1: Compliance v. complicity: The ‘underbelly’ of bank culture

- 3

- 4

- 5

No comments yet