- Home

-

News

- Back to parent navigation item

- News

- National Compliance Officer Day 2025

- Accounting & Auditing

- AI

- AML

- Anti-Bribery

- Best Practices

- Boards & Shareholders

- Cryptocurrency and Digital Assets

- Culture

- ESG/Social Responsibility

- Ethics & Culture

- Europe

- Financial Services

- Internal Controls

- Regulatory Enforcement

- Regulatory Policy

- Risk Management

- Sanctions

- Surveys & Benchmarking

- Supply Chain

- Third Party Risk

- Whistleblowers

- Opinion

- Benchmarking

- Certification

- Events

- Research

- Awards

-

CW Connect

- Back to parent navigation item

- CW Connect

- Sign In

- Apply

- Membership

- Contact

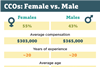

Salary data: Women getting CCO opportunities, but pay disparity pervades

By  Dave Lefort2020-09-30T18:03:00

Dave Lefort2020-09-30T18:03:00

A crunching of numbers from our “Inside the Mind of the CCO” survey showed the same gender pay disparity that pervades corporate America also exists in compliance.

THIS IS MEMBERS-ONLY CONTENT

You are not logged in and do not have access to members-only content.

If you are already a registered user or a member, SIGN IN now.

Related articles

-

Article

ArticleOn International Women’s Day, we should ‘Choose to Challenge’

2021-03-08T15:10:00Z By Aly McDevitt

International Women’s Day isn’t just about celebrating women. It’s also about challenging norms. As such, CW’s Aly McDevitt challenges you to read this piece without flinching.

-

Article

ArticleWhat’s your worth? Succeeding in compliance pay negotiations

2020-12-29T19:00:00Z By Amii Barnard-Bahn

Whether you are asking for a pay raise in your current role or negotiating compensation in a new role, executive coach Amii Barnard-Bahn offers tips to help ensure you are paid equitably for the work you do and value you bring to your organization.

-

Premium

PremiumCCO compensation data reveals big strides for women

2019-09-26T10:45:00Z By Dave Lefort

Bucking the trend: Survey shows women more likely to hold top compliance roles, have a law degree, and make a bit more money than men.

More from Compensation

-

Premium

PremiumBarclays is axing its bonus caps. Is it also ditching good governance?

2024-09-23T18:50:00Z By Neil Hodge

Four years post-Brexit, London-based Barclays became the first British bank to scrap bonus caps for its traders that were meant to curb excessive risk-taking with client cash, improve corporate governance, and restore faith in an industry most working people still hold responsible for 15 years of economic misery.

-

Premium

PremiumDisclosure rules not enough to curb U.K. salary gaps

2024-01-15T14:16:00Z By Neil Hodge

The issue of “fat cat” pay awards was reignited in the United Kingdom after a think tank found a typical FTSE 100 CEO earned the average annual salary for a full-time worker after just four days into the new year.

-

Premium

PremiumCCO/CECO salary data: Five noteworthy trends

2022-12-14T13:00:00Z By Kyle Brasseur

Chief compliance officers are earning more than before compared to previous years of our “Inside the Mind of the CCO” survey, though trends like differences in gender pay persist.

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Info

- © 2025 Compliance Week

Site powered by Webvision Cloud